Mateo’s Hoop Diary: The Mavericks dismantled the Heat at Kaseya Center

Luka Dončić uncorked the Mavericks’ offense with back-to-back triples and knocked down another tray five minutes later. He guarded himself by picking up three first-quarter fouls and sat with 13 points until nearly midway through frame two. The Heat countered, splashing four of seven deep shots and cutting up the baseline, but Kyrie Irving took over Kaseya Center.

The Heat was absent Duncan Robinson (back) and Terry Rozier (neck). The Mavericks played without Dereck Lively II (knee).

Then it got ugly. The team with “Culture” on its jerseys was pushed around and burned from distance, while its effort levels were low for the first half. The hosts trailed by as much as 25 points and were below 47-69 at halftime. Up to that moment, the Mavericks had made 12 of 17 baskets in the lane.

Jimmy Butler took it easy, attempting only five shots and committing five turnovers against the Mavericks’ defense. Bam Adebayo was the worst big man on the court, misfiring on one 3-point try and seven consecutive close-range looks against Maxi Kleber and Daniel Gafford.

The only bright spots before intermission were Tyler Herro and Caleb Martin, as the former broke into the lane for three baskets and the latter downed two triples.

Yet, the Mavericks blanking makable deep tries, and Kevin Love supplying 10 points on rim attacks and long-distance buckets opened the door for a comeback. At the end of the interval, the Heat was behind 74-88.

Then the squad deployed the zone in the fourth quarter, but the Mavs were not fazed. PJ Washington hit two shots at the heart of the scheme, Irving dribbled left past it to the rim, and Gafford scored from the dunker spot on consecutive plays.

Adebayo and Butler were subbed back in with 6:43 left as the team was down 13. Their impact to close out the game was microscopic. Adebayo missed his only attempt in the fourth quarter, but Butler made his, hoisting over Irving on the baseline.

Herro was the only Heatle to record multiple baskets in the fourth- a pair of threes that cut the Heat’s deficit to nine and eight points with under nine minutes to go. But the Mavs resisted any further comeback attempts.

Dončić dribbled into the paint and hit a fadeaway over Love on the right side; former Heatle Derrick Jones Jr. dashed by Butler and scored on Adebayo at the rim; and Irving’s left baseline drive around Herro for a left-handed layup sealed the deal.

The Heat lost 92-111. The crew picked up 36 paint points, five on the break, 14 via second chances, eight after turnovers and 23 from the bench. The hosts also had seven more rebounds and eight extra turnovers than the Mavs.

Herro produced 21 points on six of 15 attempts, with seven rebounds, six assists and four turnovers. Love had 16 on his scoring ledger on 66.7% accuracy, with 11 rebounds. And Martin put up 14 points on five of 14 looks, with four boards and six dimes.

The Mavericks had 48 interior points, 24 in the open court, seven on extra tries, 19 after turnovers and 21 from the reserves.

Dončić registered 29 points on nine of 23 tries and recovered nine rebounds, nine assists and three turnovers. Irving had 25 on his ledger, making 66.7% of his attempts, with three rebounds, four assists and two steals. And Jones and Washington had a dozen points apiece.

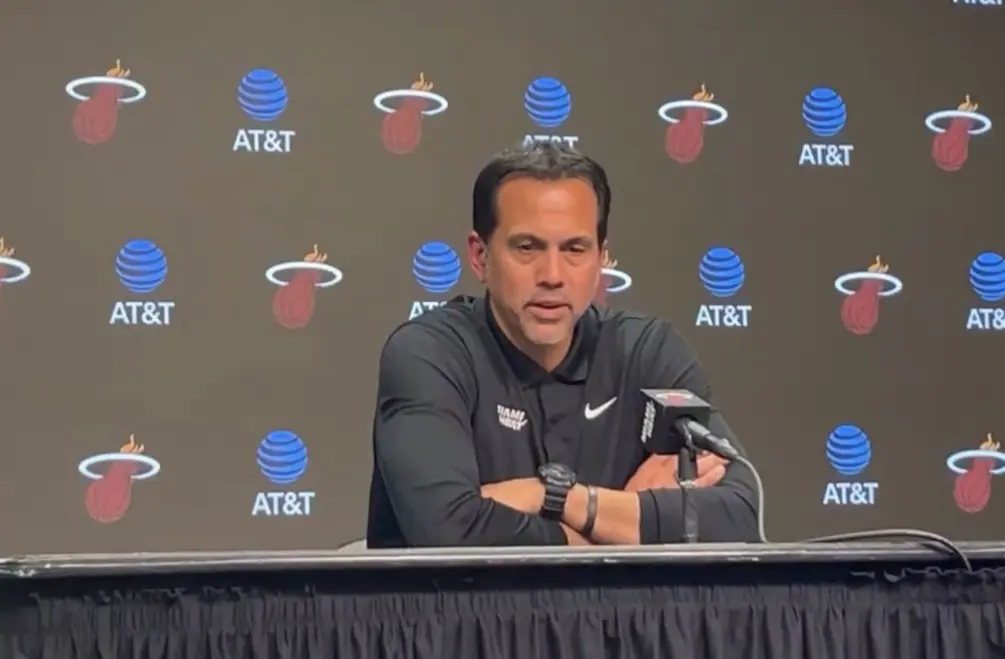

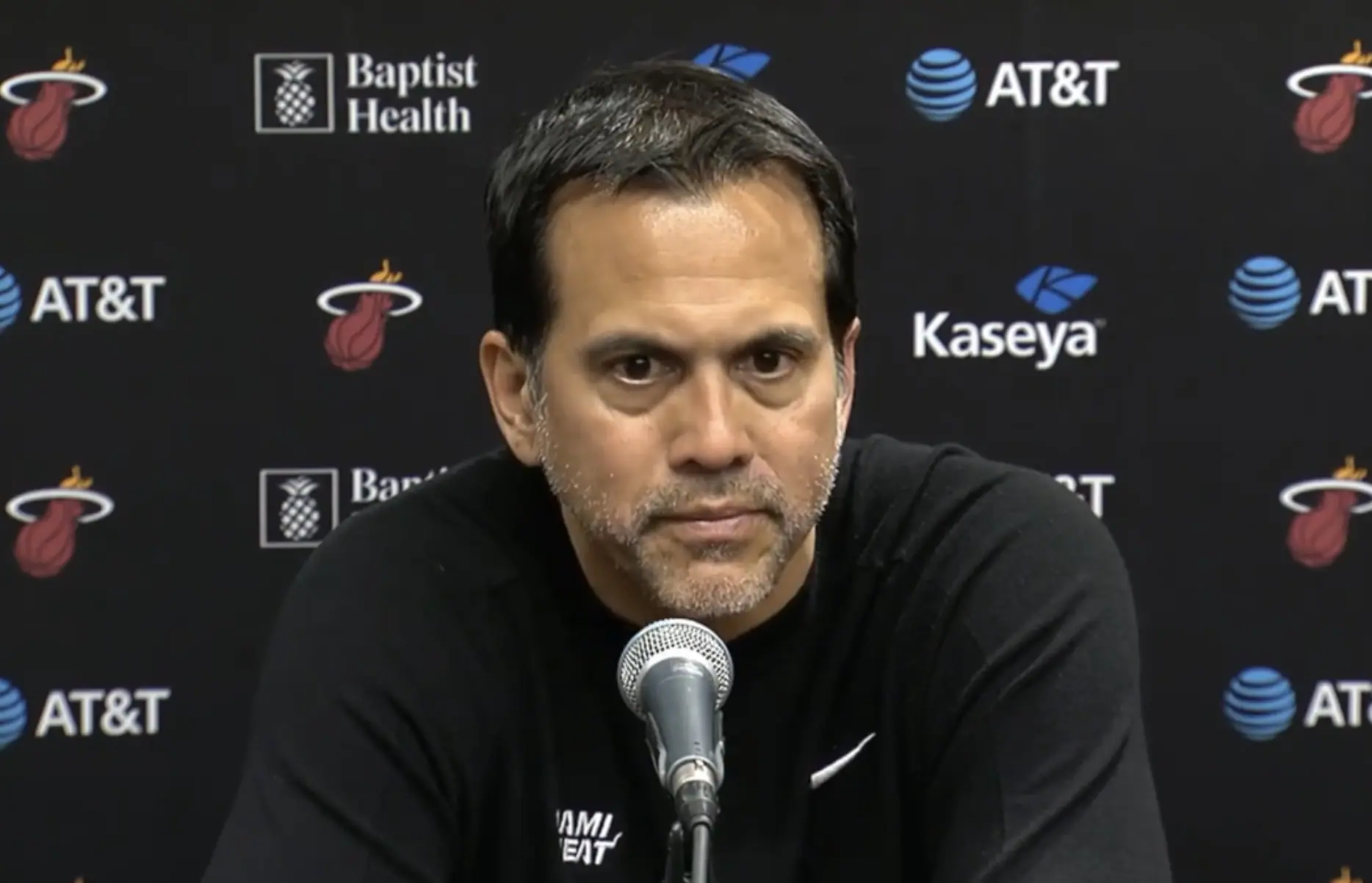

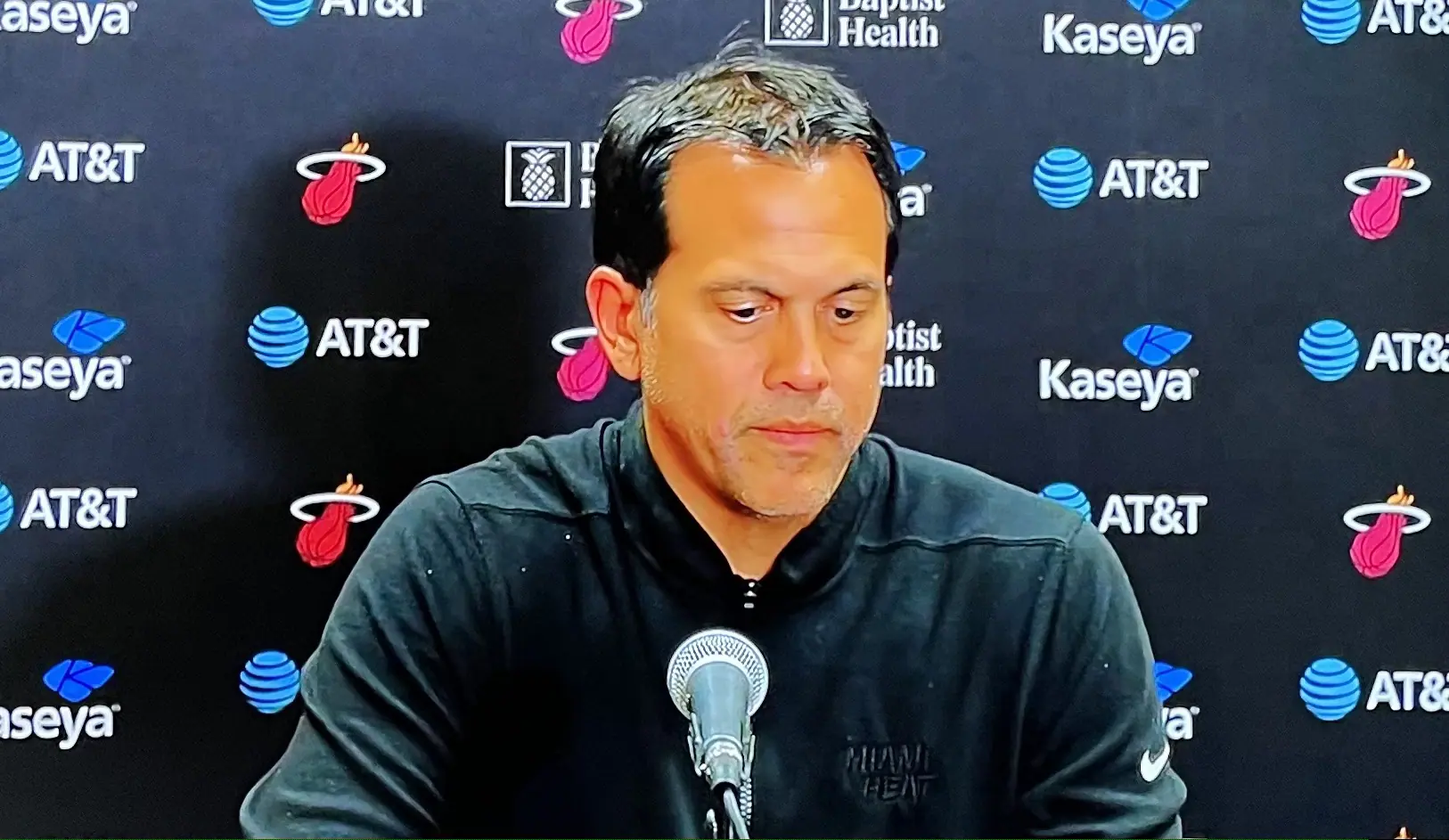

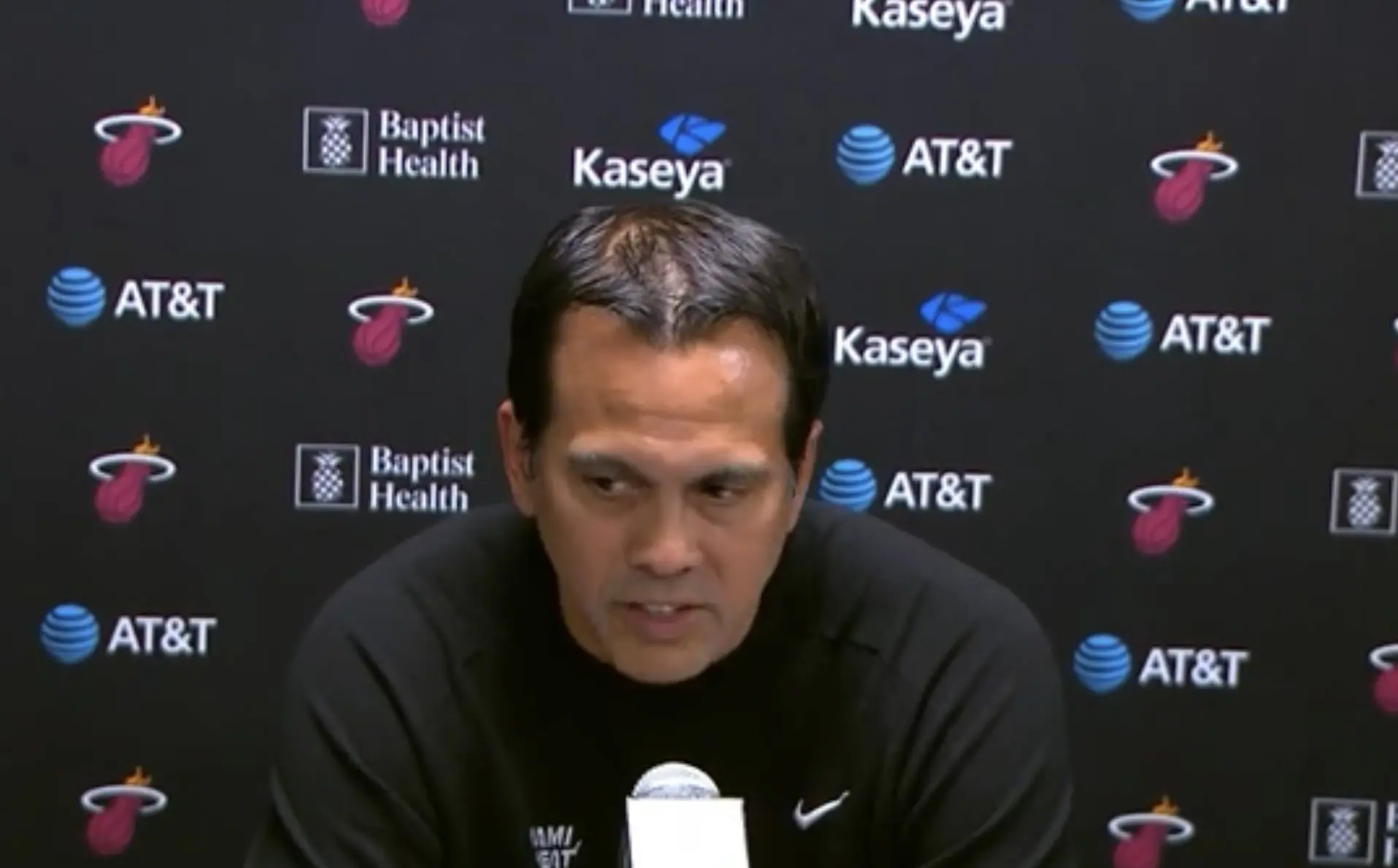

At the postgame presser, coach Erik Spoelstra said, “[The Dallas Mavericks] jumped us…sometimes this league can just really humble you and that’s what happened tonight.”

Butler did not speak to the media.

The Heat will not practice on Thursday

–

For exclusive Miami Heat content and chats, subscribe to Off the Floor: