Two of the NHL’s best will meet Wednesday night at Madison Square Garden for Game 1 of the Eastern Conference Final.

The Presidents’ Trophy winning New York Rangers (55-23-4) will play hosts to last year’s Eastern Conference champion Florida Panthers (52-24-6).

New York swept the Washington Capitals 4-0 in the first round, then took down the Carolina Hurricanes 4-2 in the second.

Florida defeated the Tampa Bay Lightning 4-1 in its first round series, then defeated the Boston Bruins 4-2, getting back to the Eastern Conference Final for a second consecutive season.

It should be no surprise to anyone that the Rangers and Panthers are two of the final four teams remaining in the playoffs. They were two of the most dominant teams all season, it’s only right that they will battle for a spot in the 2024 Stanley Cup Final.

The task at hand won’t be easy for the Panthers as the Rangers will be the toughest opponent they faced to this point.

Here’s my three keys for the Panthers heading into the series.

Win the goalie battle, beat Shesterkin

If you enjoy goaltending battles, Florida has been the team to follow this postseason.

Florida has already played against two of the league’s best goaltenders in the playoffs, facing off against Tampa’s Andrei Vasilevskiy in the first round and Boston’s Jeremy Swayman in the second.

In the conference final, it will be another goalie stans’ dream with Sergei Bobrovsky’s Panthers facing Igor Shesterkin and the Rangers.

Shesterkin and Bobrovsky have both been great this postseason and the two Russian netminders will have to do it again with the offenses they are facing in round three.

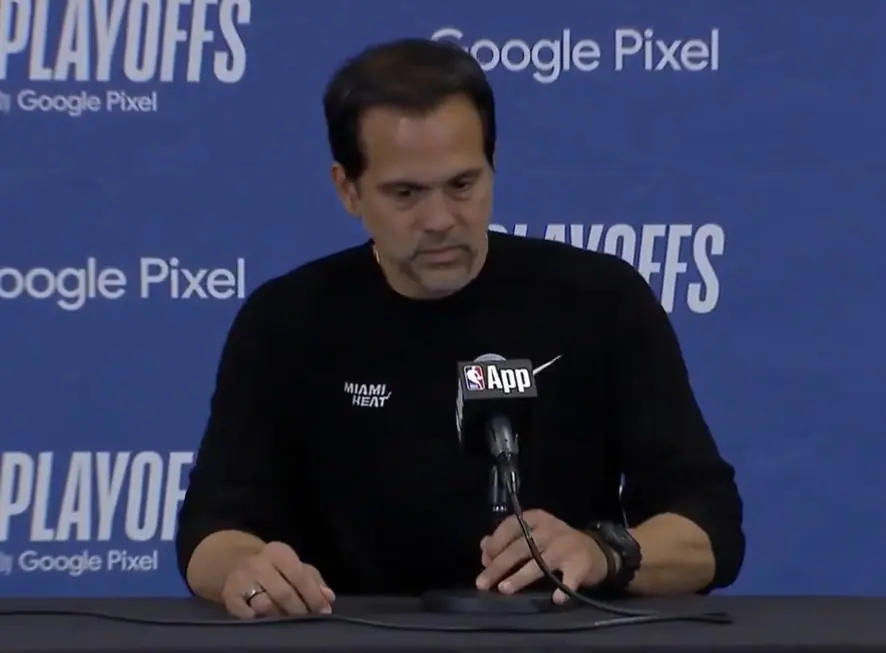

“Well it’s a great matchup, that’s probably the only part of this I can answer. I’m not lying to you,” Panthers head coach Paul Maurice said when asked about the goaltending matchup.

Maurice didn’t say that to be snarky, he has constantly made it a point that he’s no goaltending expert, he lets them do what they need to do.

“There’s some spectacular goalies from all over the world and we’ll see a matchup of two great ones,” Maurice said when trying to answer the matchup question. “It’s a theme for our playoffs because Vasilevskiy was very strong at certain points in that series and I think Swayman had a .955 at some point in our series… There’s going to be some world class players in all positions (in the conference final) and our side will have two brilliant goaltenders.”

Bobrovsky posted a 2.37 GAA and .902 save percentage so far in the postseason — playing in every game for the Panthers so far. He has conceded two or fewer goals in eight of 11 games this postseason and has been locked in since giving up four goals in Game 1 against the Bruins last round.

Shesterkin has a 2.40 GAA and a .923 save percentage in the playoffs and has had to face a lot more action than Bobrovsky, averaging 32.4 shots per game, compared to Bobrovsky’s 24. Shesterkin averaged 37.2 shots a game in the second round against Carolina.

Neither side has struggled to score in the playoffs, with the Panthers averaging 3.55 goals per game, with the Rangers right behind a 3.50.

Conquer the road

After having home-ice advantage in the first two rounds of the playoffs, the Panthers will begin the Eastern Conference Final on the road. Florida has fared well away from home this postseason, going 4-1-0 in its five road games so far. They won all three road games last series in Boston.

Last year, the Panthers made it to the Stanley Cup Final while starting every series on the road.

Between the flights, buses, dinners, hotels — you spend a lot of time with your teammates on the road. The Panthers tight knit locker room plays a huge factor into why they’ve had success away from Sunrise.

“It works for us because these guys like hanging out with each other. It’s a good place,” Paul Maurice said. “We are hyper routined in how we travel, the time we leave, all that kind of stuff. There’s a nice order to your day, when you leave town your day gets very, very ordered.”

“These guys get along great and have long before I got here and you know what it’s like traveling, it’s a good time everybody’s in a good mode, especially in the playoffs,” Maurice continued. “I don’t feel any more comfortable going on the road. If you’re asking me, I’ll take seven home games all day long, but our road game isn’t something that we fear.”

The Panthers have played and won in some hostile environments over the last few seasons, most recently in Boston. Madison Square Garden won’t be any different come Wednesday night.

“We’re the only game on the nights we are playing. There’s nobody else on so all eyes will be on us,” Panthers forward Matthew Tkachuk said. “That just adds on to the whole New York City, MSG, playing the number one team in the league. It all adds up right now, this is a very exciting time of year to begin with no matter who you’re playing. And to be playing the New York Rangers, it just adds so much to it. This is a huge stage for us, for our team.”

The Rangers haven’t been an easy out on home ice this postseason, losing just once in five games (4-1-0), but the Panthers are more than excited for the opportunity at hand.

“Not only is it the conference finals but to play in New York, I think guys are pretty jacked up about that,” Panthers defenseman Brandon Montour said.

Special teams will win the series

As the teams continue to dwindle down, every group is going to be elite at something.

We’ve already looked at the goaltending — which is fantastic for both sides.

Based on the offensive firepower the two teams have, special teams may win you a game or the series.

This series will feature the second and third best penalty kills in the playoffs. The Rangers 89.5 % success on the PK is second best in the league, while the Panthers are narrowly behind them at 86.1%.

“They obviously get chances. You’ve seen that in the last couple of rounds,” Brandon Montour said about the Rangers PK. “I don’t know how many goals they’ve had, but three or four short handed goals… We got to be ready to move the puck quick, make hard plays and be on it every power play we get.”

Florida’s PK is led by their captain and 2024 Selke Trophy winner, Aleksander Barkov. They also have Sam Reinhart, who finished fourth in Selke voting (second most first-place votes), Kevin Stenlund, Anton Lundell and Eetu Luostarinen bolstering down the PK unit.

The Panthers PK will have a lot of firepower to deal with as the Rangers have a 31.4 % conversion rate on the power play, thanks to the likes of Artemi Panarin, Vincent Trocheck, Mika Zibanejad, Chris Kreider and company.

On the other hand, Florida’s power play hasn’t been as good as they’d like it to be. scoring just 22% of the time in the playoffs — with four of their nine power play goals coming in one game.

Despite this, Florida has more than enough weapons to match the Rangers dangerous power play.

Reinhart had the most PPG in the regular season with 27, while Matthew Tkachuk had a team high 26 power play assists.

Like the Rangers, the Panthers can score with both of their power play units and they’ll need to against this New York team.

Game 1 is Wednesday, May 22 at 8 p.m. ET from Madison Square Garden in New York