Who is Next?: Five Marlins 1st Round Draft Targets

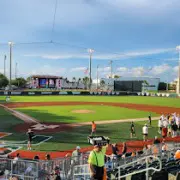

The 2023 MLB draft is just a month away, and while Marlins fans have come to expect a dose of disappointment on draft day, the Marlins have a fantastic opportunity to add offensive talent to a system that certainly needs it. Analysts within the industry have set expectations that there is a strong crop of talent available for the first 10 picks, which bodes well for the Marlins since they own the 10th pick in this draft. As you read this article, keep in mind that while there are players that outlets have ranked higher who should be available for the Marlins selection, these are the players that I think would best suit the organization.

Assumptions:

This list assumes that the top ranked draft prospects—Dylan Crews, Wyatt Langford, Walker Jenkins, Max Clark, Paul Skenes, and Chase Dollander—are selected prior to the Marlins pick. If any of them become available at pick 10 it is reasonable to assume that the Marlins will select that player.

Now without further ado, here are the five—plus an honorable mention—draft prospects who I believe that the Marlins should target in the 2023 MLB draft.

Honorable Mention

Kyle Teel (C, Virginia)

MLB Pipeline Draft Ranking: 10

Pipeline Scouting Grades: Hit: 55 | Power: 45 | Run: 50 | Arm: 65 | Field: 50 | Overall: 55

When it comes to draft helium, no one has skyrocketed up the rankings as much as Kyle Teel, who went from being a fringe first round selection back in March to an almost assuredly top 10 pick now in June. I’ve listed Teel as an honorable mention because at this point, analysts are confident that he will be selected within the first 8 picks of the draft. With that being said, if he is available at pick 10, then the Marlins absolutely need to pounce and select him.

A full-time starter since his freshman year, Teel has separated himself as the clear-cut top catcher in this year’s draft thanks to an incredible Junior season where he slashed .423/.487/.690 and struck out just three more times than he walked. It’s an above average hit tool with solid power on the offensive side, a profile that is similar to Henry Davis, who was selected first overall by the Pirates in 2021. With Teel, you won’t get the exit velocities that pushed Davis to the top of the draft, but you will get a hitter who doesn’t chase, doesn’t whiff, and can still produce exit velocities that exceed 100 MPH.

Not only can Teel mash, but he’s also a very capable defender who will stick behind the plate as a pro. He’s an elite athlete with a plus arm, strong leadership skills, and a high baseball IQ. His athleticism has allowed him to play the outfield in addition to catcher, and some scouts believe he could play second or third base if needed.

It’s no secret that the Marlins are desperate for catching talent, and while you aren’t supposed to draft for need in the MLB draft, selecting Kyle Teel would check the boxes of drafting both the best player available and a player who fulfills a position of need in the organization.

- Chase Davis (OF, Arizona)

MLB Pipeline Draft Ranking: 39

Pipeline Scouting Grades: Hit: 45 | Power: 55 | Run: 55 | Arm: 60 | Field: 50 | Overall: 50

HAHAHA OH MY GOD CHASE DAVIS JUST HIT ONE OF THE FURTHEST BALLS OF THE BBCOR ERA

Don’t be shocked if you see his name called in the Top 5 picks of the MLB Draft this year pic.twitter.com/1nLLSs8D6K

— 11Point7: The College Baseball Podcast

(@11point7) May 27, 2023

Chase Davis is as polarizing of a prospect as it gets. Some outlets have him ranked in the 20’s or 30’s due to concerns surrounding his hit tool—Keith Law didn’t have Chase Davis selected in The Athletic’s first round mock draft at all. Other outlets have him surging towards the top 10. It’s a natural lack of industry consensus considering the type of season that he’s had. After hitting .289 with a 23% strikeout rate his sophomore year, Davis turned his bat into a lightning rod for his junior season and hit .362 with 21 home runs while lowering his strikeout rate to just 14% and walking 15% of the time. If you watch Davis hit, you’ll notice his mechanics look identical to that of Carlos Gonzalez, and his profile is quite similar too.

With Davis, you’re looking at a corner outfield masher who will whiff his fair share but will also rip off some of the higher exit velocities for the team that drafts him. He’s been clocked with a max exit velocity of 115 MPH, and his 90th percentile exit velocity sits just below 110 MPH, per Mason McRae. His incredible bat speed allows him to realize his full raw power in-game. Despite the concerns surrounding his hit tool, Davis has certainly quieted concerns with the reduction in strikeout rate and chase rate (82nd percentile in chase rate, per Mason McRae). In the outfield, Davis has demonstrated an above average arm, which will allow him to play above-average defense in either corner. While he played only in the corners this season for Arizona, he did play some center field during the Cape Code League in 2022.

I have Davis as my top draft target for the Marlins because of the prolific offensive upside he possesses. He hits the ball as hard and as frequently as top draft prospects Dylan Crews and Wyatt Langford, and he’s made incredible strides to improve his hit tool, which is now closer to above average than it is below average. He can run, he can throw, and he brings the upside of the coveted 5-tool profile. I mean, look at this power [insert linked video]

- Arjun Nimmala (SS, Strawberry Crest HS)

MLB Pipeline Draft Ranking: 9

Pipeline Scouting Grades: Hit: 50 | Power: 55 | Run: 50 | Arm: 55 | Field: 50 | Overall: 55

It’s difficult not to love this swing from 2023 SS Arjun Nimmala.

In-rhythm, creates separation, elite bat speed, and ability to create loft with ease. Massive power potential at a premium defensive position for the @FSUBaseball commit. #MLBDraft @PBR_DraftHQ @ShooterHunt pic.twitter.com/Rbq97lCR35

— Ian Smith (@FlaSmitty) April 19, 2023

Arjun Nimmala has some of the highest upside in the entire draft and it wouldn’t be out of the question to go in the first five picks despite not being ranked as high as some of the other talents ahead of him. At 6’1, 170 pounds, Nimmala has the toolset for you to dream on, with the ceiling of an elite MLB shortstop. He has a picturesque swing, which helped him accumulate a .479 batting average and a .573 on-base percentage during his senior season. While the game power hasn’t come in as much as analysts had expected, his frame suggests that there is more in the tank.

Defensively, scouts laud his quick actions and strong arm, which should allow him to remain at shortstop as he develops in the minor leagues. Just as the Marlins were able to capitalize on the crop of elite shortstop talents in the 2021 draft, which included Marcelo Mayer, Jordan Lawler, Brady House, and Kahlil Watson, they have the ability to dip their toes yet again in the high school shortstop ranks and bolster their organization with young offensive talent. We’re talking about a fantastic athlete who hits the ball and hits it hard, which is exactly what you want from a high school prospect.

Nimmala represents the high-ceiling/low-floor pick for the Marlins, but if they can develop him the right way, they could have a future star on their hands.

- Tommy Troy (SS, Stanford)

MLB Pipeline Draft Ranking: 19

MLB Pipeline Scouting Grades: Hit: 50 | Power: 50 | Run: 55 | Arm: 50 | Field: 50 | Overall: 50

Tommy Freakin' Troy (That's his legal name)pic.twitter.com/ZY50iLfz6J

— Joe Doyle (@JoeDoyleMiLB) June 4, 2023

You know when you take a bite of one of those mini pizza pockets, and all of the pizza filling bursts out of the pocket and burns your tongue? That is basically Tommy Troy. He’s a massive punch packed in a 5’10 frame, as evidenced by his 17 home runs and .747 slugging percentage. The starting shortstop for Stanford, one of the premier teams in college baseball this season, Troy has cemented himself as one of the top hitters in this draft. He hits for average (.413 batting average), power, and he can run the bases (17 steals on the season). His extremely fast hands allow him to make contact on pitches that he chases, which helps him make up for his poor swing decisions. While that could become an issue in pro ball, he has the tools and years of development to get by (how does 110 MPH exit velocity sound from your 5’10 infielder?).

While Troy might not be a sure-fire shortstop in the pros, Keith Law told me that at worst he sees Troy moving over to third base where he could become a capable defender. He’s also spent time at second base and left field during his time at Stanford. Troy’s athleticism should allow him to add value all around the diamond even if it isn’t at shortstop every day.

What I love about Troy is that he not only dominated PAC12 baseball, but he also was one of the top performers in the Cape Cod league last season. The significance here is that the Cape league uses wood bats, so Troy proved to scouts that he can handle a wood bat when he slashed .310/.386/.531 in Cape Cod. He’s going to hit and hit his way into a starting second base job in the pro’s. And while I don’t love putting pro comparisons on college players, I think that he’s someone who could develop into an Ozzie Albies type of infielder.

- Noble Meyer (RHP, Jesuit HS)

MLB Pipeline Draft Ranking: 11

MLB Pipeline Scouting Grades: Fastball: 60 | Slider: 55 | Changeup: 50 | Control: 50 | Overall: 55

Noble Meyer (‘23 OR) just simply electric here for @jhsbaseball503. Sitting 95-96 & doing it easy, SL @ 31-3200 RPMs (clip) is ridiculous, highest level ceiling & top of the class stuff. #Oregon commit. #PGDraft @PG_PacificNW pic.twitter.com/Nps9KxAiLE

— Perfect Game Scout (@PG_Scouting) March 29, 2023

How can the Marlins find a way to avoid a hitting developmental disaster in the first round of this year’s draft? By drafting a pitcher! We’re dipping into the prep school pitcher ranks here for the next option, an area where teams in the top 10 rarely go. However, when the player has the polish and the stuff that Noble Meyer has, you go and get him. Meyer hails from the same high school that recent top prep pitcher Mick Abel came from. And funny enough, they’re very similar pitchers. Meyer has a tall frame at 6’5 with plenty of room to fill out. He’s already touching 98 MPH on his sinker, and he’s got a sweeper that Mason McRae labels as one of the best pitches in the draft, citing a spin rate that nearly reaches 3,000 RPM’s. For context, Jackson Jobe, who the Tigers selected with the third overall pick in the 2020 draft, was drafted practically for his 3,000 RPM slider alone. Meyer pairs that devastating pitch with his elite sinker and a passable curveball, so you can see why he’s a tantalizing prospect.

This is a pick where the Marlins can really make their mark. As an organization, they’ve proved their ability to identify and develop pitching. Adding an elite arm like Meyer into the system will only bolster their talent pool. The organization is known for helping pitchers develop lethal changeups (see Jesus Luzardo, Sandy Alcantara), and if they can do the same with Meyer then it should give him four plus/double plus pitches to pair with an advanced feel for pitching. While selecting high school pitchers always carries risk, this is one of the safer prep arms in the last few years, and it could end up paying off as Meyer carries a real possibility to develop into an ace and move through the system quickly.

- Matt Shaw (SS, Maryland)

MLB Pipeline Draft Ranking: 18

MLB Pipeline Scouting Grades: Hit: 55 | Power: 55 | Run: 60 | Arm: 45 | Field: 50 | Overall: 55

Matt Shaw hit this ball 507 ft. Yes you read that correctly pic.twitter.com/1LcCObVTu6

— Stephen Schoch (@bigdonkey47) March 31, 2023

Remember when I said that Tommy Troy was one of the best performers in the Cape Code League? Well, Shaw was THE best hitter in the Cape, slashing .360/.432/.574. To put that into context, Jacob Gonzalez, one of the top college infielder prospects in the draft, didn’t even put up those numbers this season, and that’s with metal bats. Shaw is a professional hitter who will hit wherever he goes. I mean, just look at these numbers:

| AVG | OBP | SLG | OPS | |

| College Career | .320 | .413 | .623 | 1.036 |

| Cape Cod Career | .364 | .450 | .672 | 1.122 |

Whether it’s metal bats or wood bats, the guy has just continued to hit since he turned 18 years old. Oh yeah, he also hit 24 home runs this season, including a BOMB against Iowa that traveled over 500 feet. So why is Shaw not the top target for the Marlins in this draft? He’s currently a shortstop, but the industry consensus is that he is clearly a second baseman as a pro. So, the lack of positional value does hurt him here a bit, but this is such a safe profile of a premier offensive second baseman that I really don’t care about the position. From an offensive standpoint, this is the perfect package of bat-to-ball, power, and plate discipline and I’m a bit surprised that outlets don’t have him ranked higher. He very well might not even make it to pick 10. If I had to put my money on any college hitter in this draft after Crew/Langford to become an All-Star, I would throw it all on Shaw.